-40%

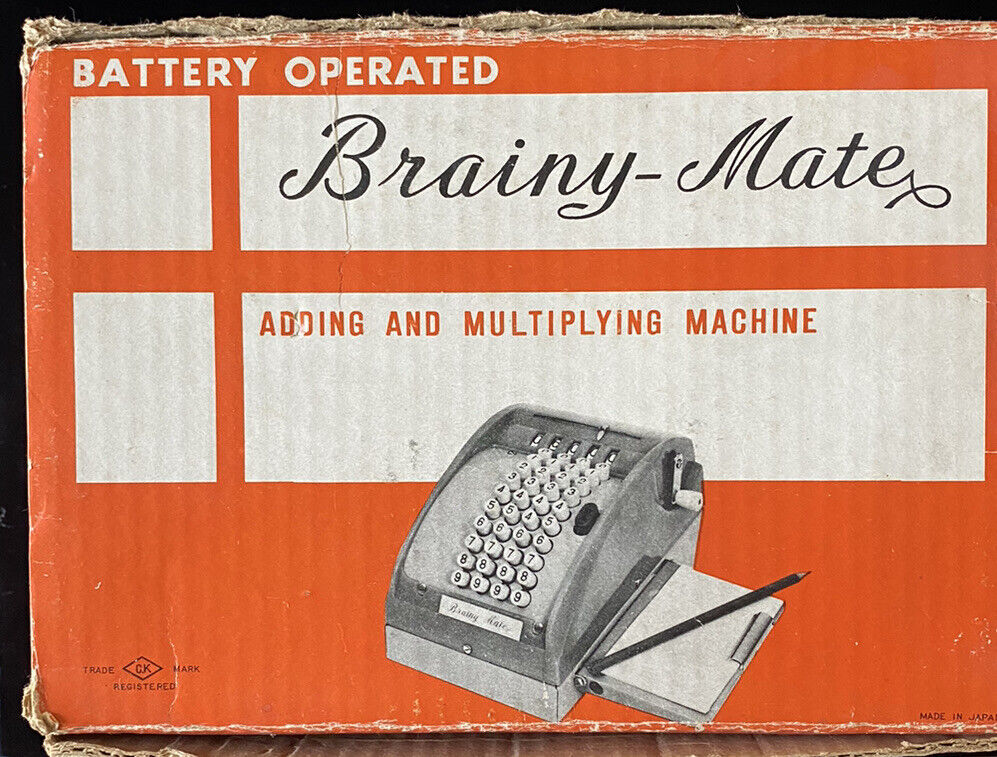

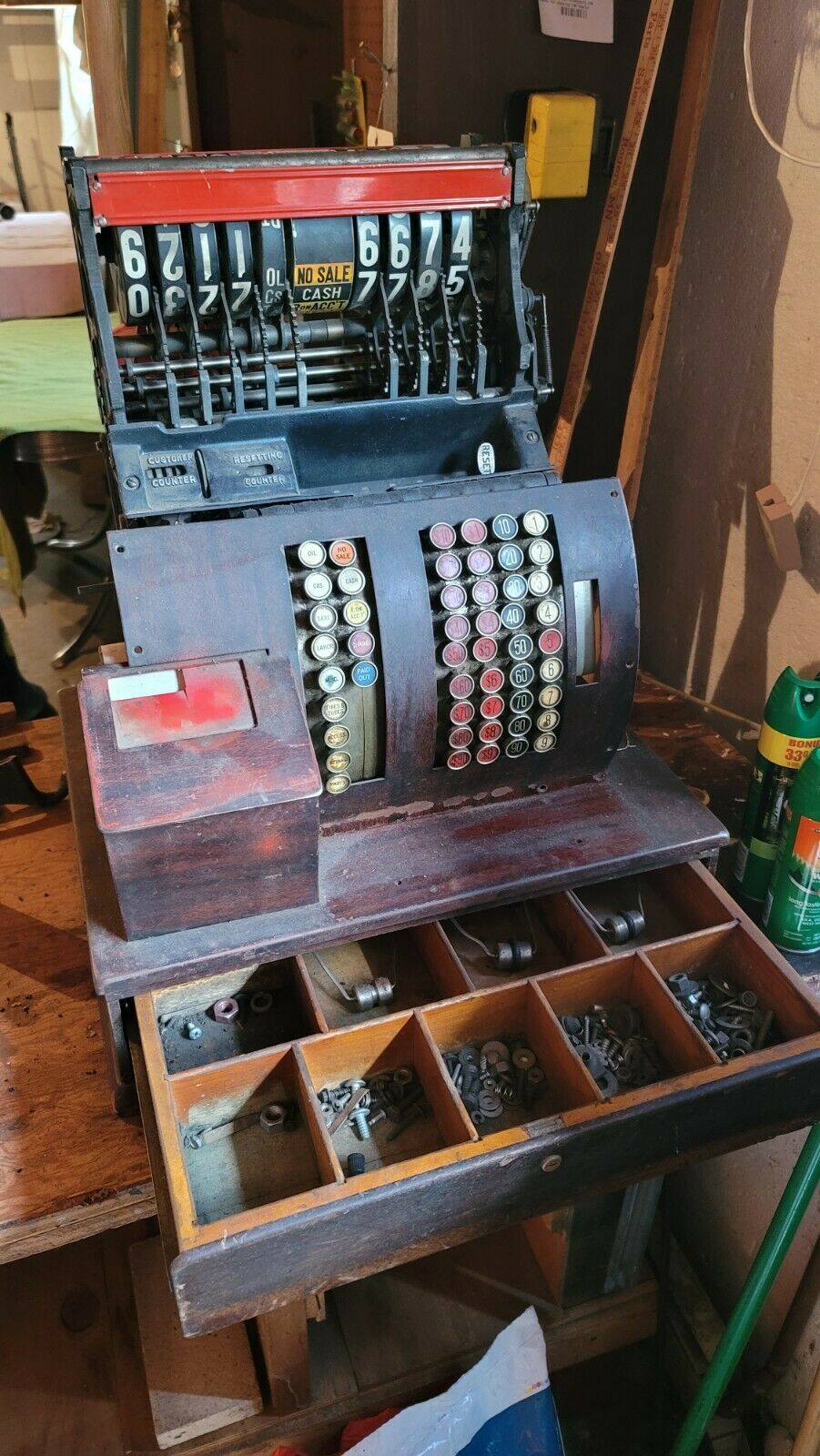

Antique 1930's Westinghouse Merchant Calculating Machine

$ 211.2

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

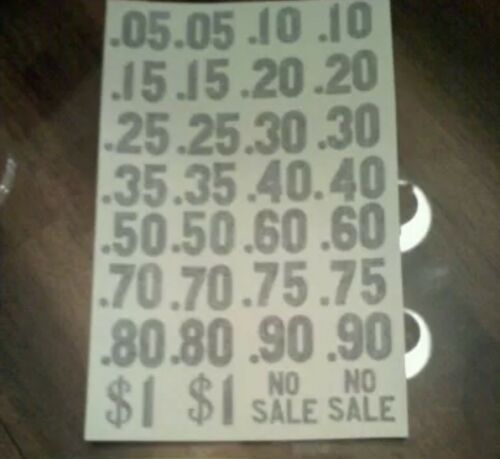

This calculating machine is a piece of history! Read about how calculating machines evolved and why they were necessary below. Unfortunately, one of the motor cables is broken, so I can not properly test this unit without repairing that cable. The motor fan turns freely and the buttons all press and release. I think this unit would be fully functional with some cable repair. There are several of these machines listed currently on eBay, with the lowest unit priced at 0 and the highest at 00!This full-keyboard, non-printing electric pinwheel calculating machine has nine columns of plastic keys, colored according to the place value of digits entered. At the base of each bank of keys is a red clearance key. The underlying keyboard is painted green. Between banks of keys are metal rods for decimal markers. To the right of the keyboard are bars for subtraction and addition; a red ADD key, depressed for automatic clearance after each operation; and a stem for a clear key (the key is missing). Still further to the right is a column of nine keys for automatic multiplication. Left of the keyboard is a switch for the motor. Behind the keyboard is a movable carriage with 18 windows for the result register. Above this is a nine-digit entry register and a nine-digit revolution register. Clearance keys for these registers are to the right. At the back of the machine is the electric motor. The machine has an aluminum base and four rubber feet.

If you have any questions, please don't hesitate to ask!

History:

At the turn of the century, the big corporation was pioneering more sophisticated ways to produce and distribute goods and on a much bigger scale. This required an army of employees whose job was to handle data. Regulating the corporation also required establishing routines, and even routines for those establishing the routines: a pyramid of bureaucracy. This bureaucracy created new professional careers, particularly for women. By 1900 about 12% of the working population in the USA was employed to handle data, as compared with 25% in manufacturing. The railroads were again the pioneers in adopting office equipment to handle data: equipment for communications (the telegraph and the telephone), for writing letters (typewriter), for collecting data (tabulators) and for calculations (adding machines). The mechanical calculating machine had existed since at least 1851, when Thomas de Colmar (who had originally conceived it decades earlier) had successfully demonstrated his "arithmometer" at the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851 and started selling it (Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace's analytical engine, that was designed to use Jacquard's punched cards, was never built). Several clones surfaced in Germany (by Arthur Burkhardt since 1878) and in Britain (by the brothers Charles and Edwin Layton since 1883), while Colmar's engineer Louis Payen took over the original French firm in 1887. Before the invention of calculators, scientists and engineers own volumes of tables. One could simply look up the result of a mathematical operation, whether a multiplication or a logarithm. Those tables were made by humans and contained countless mistakes. Therefore people like Charles Babbage in England tried to build machines capable of calculating those tables automatically. Pinwheel calculators based on Colmar's arithmometer were "invented" in 1874 by Frank Baldwin in St Louis and in 1874 by Willgodt Odhner, a Swedish designer of industrial machines living in St Petersburg (Russia). The latter was mass produced after 1890 in Russia and after 1892 in Germany by Brunsviga, a sewing-machine company was already selling Baldwin's machines. These machines were smaller than the bulky Colmar type but much smaller, occupying only the corner of a counter. The next step was the simplification of input and output. In 1885 William Burroughs in Missouri developed his adding machine and founded the Arithmometer Company, and in 1886 Dorr Felt in Chicago introduced his "comptometer". Burroughs' main innovation was the "lister" coupled with the "adder": his machine printed the result. Felt's main innovation was the key: the arithmometer used a dial, and other adding machines used levers, but Felt's comptometer used columns of numbered keys. Previous arithmometers required setting levers and then turning a crank, a rather awkward operation. By the year 1900 Burroughs and Felt were the dominant players in the desktop calculator market. Railroad and banks were the early adopters, followed by government agencies.These calculators were unable to perform a direct multiplication: they calculated multiplication as repeated additions. The rise of the mechanical calculator paralleled the rise of the big corporation: until the financial panic of 1893 these inventors struggled to find a market, but towards the end of the decade their revenues skyrocketed. Not only did calculator speed up calculations, but it was also infallible. Two companies came out of St Louis (Missouri) in 1903 with a new invention, that was to become a sensation during the 1904 World's Fair in St Louis: the ten-key adding machine. The comptometer had several columns of nine keys: it was heavy, costly and cumbersome. The ten-key adding machine had simply the 10 keys set on one row, plus one row with nine tabulator keys. By 1907 Standard's machines could also add fractions, subtract, multiply and divide.Other companies soon joined the ranked of the adding machines market, notably DeKernia Hiett's Universal Adding Machine and Halcolm Ellis' company that sold Nathan Perkins' adding machine that would evolve in a combination adding machine and typewriter (marketed by the renamed Ellis Adding-Typewriter Company), making St Louis (known as "the fourth city" at the turn of the century) the center for this burgeoning industry. Finally, the adding machine got electrified at the beginning of the new century, when lamp sockets were becoming more common.

For the full history and article from where I gathered this data, visit this website: https://www.scaruffi.com/science/elec2.html